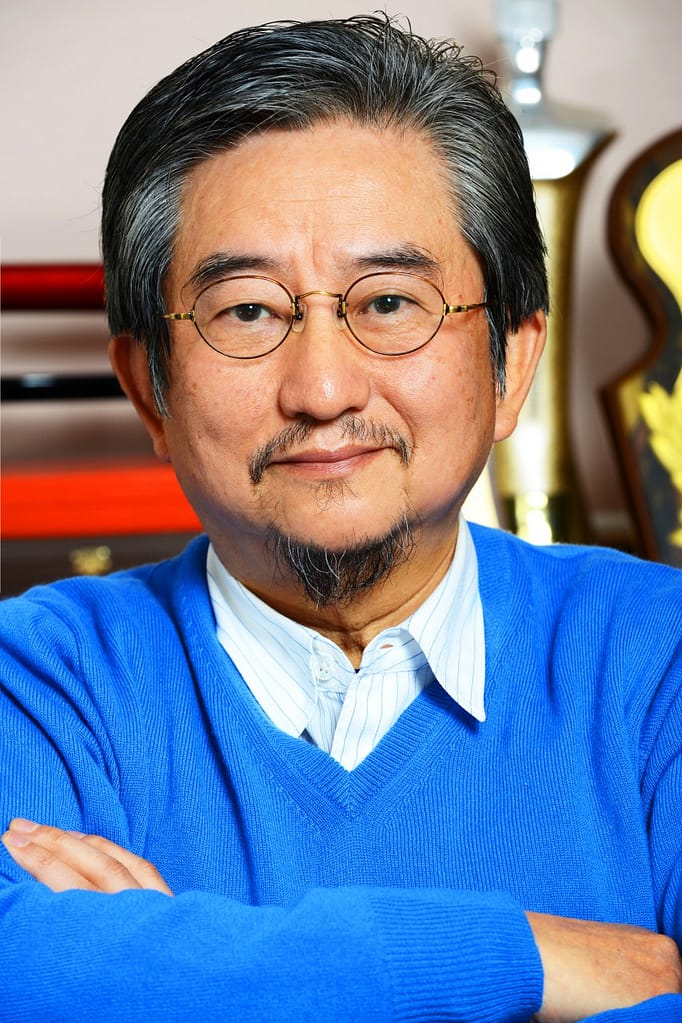

GO NAGAI:

Creator of Grendizer, Mazinger and many Japanese animé

by Sherif Awad

Comic magazines had major influence on many generations all over the 20th century until nowadays although parents sometimes tried to prevent their children from reading them to focus on their school lessons. Monthly published by DC and Marvel, American comics like Superman and Spiderman were reflecting American sociopolitical ideologies– the superiority of the American superhero over the others while establishing its image as the world savior. In Europe, in the aftermath of WWII, Belgium also rise up with publishing houses like Dargaud, Lombard and Casterman and weekly magazines like Tintin and Spirou that featured more realistic down to earth characters influenced by western culture and movies. It was called cinema sur papier (Cinema on Papers) with still ongoing characters like XIII (a secret agent inspired by the Bourne Identity novels, recently adapted as a series for American networks ), Ric Hochet (a contemporary Sherlock Holmes) and the American cowboy Lucky Luke.

In the Far East, comics took another completely different turn to reflect the ancient culture and heritage as well as the dreams and aims of this part of the world. Japan Animation (Anime) started all the way back in the 1930s then it was fused with on another Japanese art form called Manga (Japanese Comics) in order to address the public, young and old, with coherent plotlines. In the 1950s, the leading figure in Japanese Manga was Tedzua Osamu whose work was later transferred to TV with the series Astro Boy in 1963 that caused a great boom in Animation. One of the Manga artists who later grabbed the attention was Go Nagai who produced great diverse and unconventional work that found great success not only in Japan but spread in the rest of the Western world only to reach Egypt and the rest of the Middle East. Born Kiyoshi Nagai on September 6, 1945 (about a month after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima), he was influenced by many Japanese artists including Tedzua Osamu.

Nagai accidentally decided to pursue an artistic career when he fell sick for several weeks during his teen years and was falsely diagnosed with Colon Cancer. Expecting that he might die, the young Nagai went to draw some Manga characters to leave a physical trace of himself in the world. When he was cured, Nagai knew that Manga and Animation are his destiny. Nagai was the first one to unify the relationship between Man and Robot creating what’s known as Mecha (Robots controlled by a Pilot) even before the release of Steven Spielberg’s A.I. (2001) which introduced us to this term. As a result of great acclaim and popularity, Nagai’s Robots like Mazinger and Grendizer became very recognized all over the world pushing in a similar way other Japanese Anime film and series created by other artists to great successes like Spirited Away and Pokeman and even creating feature film adaptation like Crying Freeman, Transformers and Blood: The Last Vampire. While making an appearance in a French event dedicated to Animation, Go Nagai was addressed by a lady attendee from Arab origins who spoke out about the popularity of his TV series Mazinger and Grendizer in Arab countries. Astonished by this info, Nagai who never knew that his work was also dubbed in Arabic, decided to make an Arab tour of lectures and workshops for young animators in Jordan, Syria, Dubai and Egypt. His lecture in the Creativity Center at the Cairo Opera House attracted hundreds of fans who were the first to take a glance a sneak preview of the new Shin-Mazinger series, a retelling of his classic creation Mazinger Z. With a Japanese translator, I succeeded to make this conversation with Nagai, asking his questions I had since I was a kid watching Grendizer and Mazinger on my 8mm projector.

I want to ask you about your first drawings when you were a child. Were they affected by any childhood experience in the aftermath of Hiroshima? We remember that Count Brocken, one of Dr. Hell’s officers, (Mazinger’s nemesis) was an ex-Nazi.

I have been asked the same question about Dr. Hell several times here in the Middle East, but I’d like to point out that Dr. Hell is not supposed to be German. I would never associate the “bad guy” to a particular nation, because it would be unfair to the people of that country. I mean, we have already seen many Hollywood movies where the bad guys were sometimes Russians, sometimes Arabs, and I don’t really think this has helped in spreading understanding between cultures. Having said this, the war experience surely affected my whole childhood and the formation of my personality. Even if I have not experienced any bombing or fight, all the adults around me kept telling me horrible stories about the war, so I grew up with a feeling of strong rejection against it, as well as the conscience that my works should have delivered a message of peace. That is also why I was particularly saddened when I found that in many countries I was considered an author who loves to depict battles and destruction just for the fun of it. Nothing could be more different from my real stance. The reason why I depict the effects of the war in my comics is because I strongly believe that a person should learn since his childhood how much war can be destructive and how much people and societies may suffer from it, just the same way I learnt it from the stories of adults around me when I was a little child. I mean, if we raise a child telling him only the nice and happy things of life, he will be unable to cope with all the hardships he will inevitably meet in his adulthood; and if he doesn’t know the devastating effects of violence and repression, he could recur to them and cause incredible damage and sufferance to the people around him. I guess this is one of the reasons why Japanese people, who have been raised during the last sixty years reading comics that somebody abroad have labeled as “hyper-violent”, chose to be involved in no war after 1945 and have stated on their very Constitution that they renounce to war; at the opposite, a country like the U.S., where there is a strong censorship against violence in animation and programs for children, has been at war for most of his recent history. Also, Japan enjoys one of the lowest crime rates in the world, totally opposite to the U.S. This proves how violence in animation is not related at all with violent behavior in real life.

Definitely, I do believe that the influence of the war has affected the contents of my stories and my personality as a whole, much more than affecting my drawing style. Portraying wars between good and evil must eventually teach us about peace.

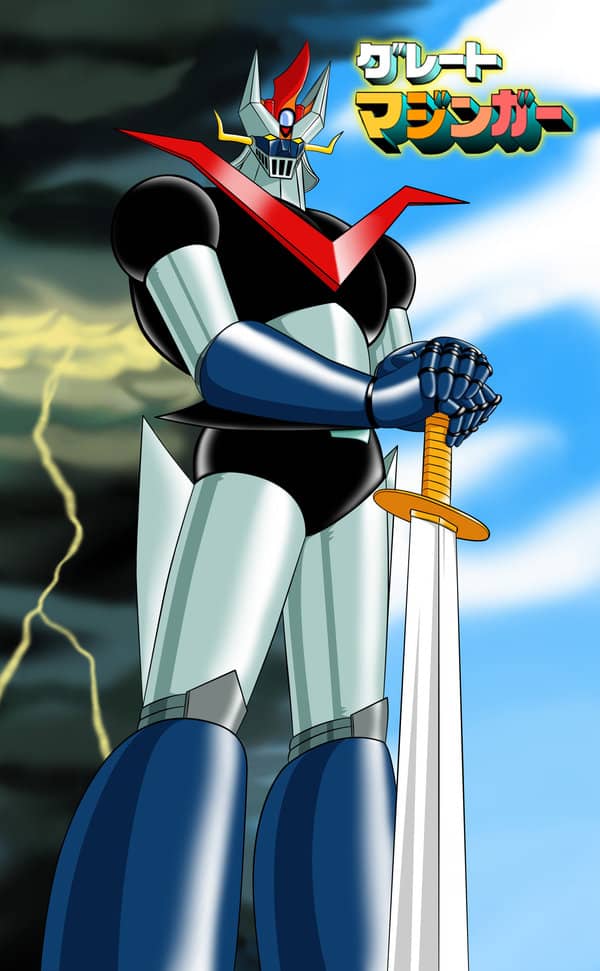

How did the characters of Mazinger and Grendizer come into shape in your imagination?

Having read and watched many Manga in my younger years, my first inspiration was the series Astro Boy about a robot in the shape of a young child (1963) by our master Osamu Tezuka and the series Gigantor (Tetsujin 28-go, 1964) about a remote-controlled robot by our master Mitsuteru Yokoyama. Five years after I decided to work as a professional Manga artist, my challenge was to create my own robot stories without imitating these two masters and their work of creation. One day, I was driving along the streets of Tokyo in the middle of a traffic jam where all drivers were sharing a common feeling of anger because they cannot move at all. At that, an idea clicked and I started to imagine that my car generated arms and legs to surpass all the other cars with man controlling it like a car from a space inside its head. I returned to my studio and started to draw and design the first prototypes for Mazinger, three times bigger than humans with its conductor Koji Kabuto riding a flying Spazer that settled down on its forehead. After six months of its first publishing as a Manga, Mazinger was acquired by TV producers to become a successful and popular series of 92 animated episodes that ran from 1972 to 1974. I think that one of the reasons for which young children loved Mazinger and Grendizer that they gave them the imagination of growing up very fast and accomplishing astonishing things.

Do the names of your characters have certain significance from Japanese culture?

In Japanese language, Mazi means magical supernatural powers like those described in One Thousand and One Nights. There were inspiration from other mythologies too; Dr. Hell’s robots were made of ruins of pre-Greek titans on an Island similar to Rhodes. Because I favored non-Japanese films, namely American and French, I chose a universal non-Japanese look for the characters although they were Japanese. It also is easier to show facial reactions on the aesthetics of such characters. Moreover, their names reflected what they do: In Japanese, Koji means helmet of samurai. When I came to Egypt, I noticed Egyptian looks similar to Koji and Daisuke (laugh).

In your more adult work, you introduced sensuality into Manga and Anime. Later on, this has acquired a cult status worldwide. Can you elaborate on this topic and also on the rise of graphic violence and erotica in Manga and Anime.

This is another difficult question. I know that many Manga works are often labeled as “erotica” in non-Japanese cultures, but once again we must keep in mind some peculiarities of my country’s culture.

In Japan, we believe that “nudity” and “erotica” are two totally different things. The Japanese people have no problem with the first issue: as you probably know, in Japan we have a lot of hot springs and public baths, and we love them. In these places, we have no shame to get completely naked in front of people we don’t even know; before the war, which means before western culture was largely imposed over the Japanese population, it was normal for men and women to get completely naked and share the same hot spring or public bath with complete strangers. In other words, during centuries for Japanese people it was totally normal to show their nudity to strangers of the other sex, and even today it is normal to show it to persons of their same-sex, because nudity is considered a natural status of the human being. I know that it can sound a bit peculiar to non-Japanese, but I guess different societies have different attitudes toward particular aspects of the human body. For instance, in China they would not share this Japanese view of nudity as natural, but their public toilets are not separated by walls, and people would line up together and chat with each other while defecating. Even if for the rest of the world this sounds extremely strange, for Chinese culture it is normal, just the same way that nudity is normal for Japanese culture.

So, some of my comics deal with nudity, but it must be considered under this point of view: they are a product of my Japanese culture and targeted to Japanese people who share the same culture, and I would never dare to diffuse them or, worse, try to impose them to cultures who have a totally different point of view on nudity. I know that in such cultures, which usually do not distinguish between “nudity” and “erotica”, they would be labeled as “erotica”, but this would be a total misunderstanding of their real essence.

Of course this doesn’t mean that in Japanese arts, including comics targeted to adult audiences, there isn’t a wide market of erotica, as there is in most countries of the West and of East Asia; it is also true that more and more, Japanese publishers try to impose erotic elements in normal comics, even when they’re targeted to young readers, hoping that such elements would help the comics to sell more. I do not agree with this policy of inserting erotic elements in stories where there is no need for them, because I strongly believe that an author should always be totally free to develop his story without being imposed any restriction by a publisher; but at the same time it is also true that at the basis of Japanese culture there is the concept that any person is free to choose what he or she wants to watch or read. There is an incredible variety of genres in Japanese comics, including erotica, but at the very end it is only the reader, upon his own responsibility, who chooses what he wants to watch and buy and to decree the success or failure of a comic book.

In the same context, you have introduced the dual masculine/feminine villainous characters like Baron Ashura. I want to know what inspired him to create such neo-Frankenstein creatures and if you would like to explore these creations in more adult work.

The idea of Ashura, the dual masculine/feminine character, actually springs out of an intuition which has nothing to do with sexuality and much with psychology. Ashura represents the average Japanese worker (but probably not only Japanese) who finds himself at the very middle of the structure of a company: he has a team of workers who obey to him, but he also has a boss to whom he has to report. I found it very funny to see people like these, who are very harsh and abusive to their staff, but when they are in front of their bosses they are completely subdue. That is why in the comic I drew, when Ashura speaks to Dr. Hell, he always uses his female ego and he’s very remissive, but when he gives orders to his staff he uses his male voice and loves to be rough and cruel!

You have also explored Machine/Human fusion in his both Grendizer and Mazinger Sagas. Many other filmmakers like David Cronenberg explored similar topics; namely in his classic films like Crash (Man vs. Cars), Videodrome (Man vs. TV) and Existenz (Man vs. Virtuosity). What does you think of this adult approaches to this fusion especially since he is a fan of non-Japanese films?

Mr. Cronenberg explores the theme of fusion between man and machine in a very philosophical and complex way, but my concept is far simpler. My robots are machines, but when the pilot gets inside them, they become his flesh and blood: when a robot is hit, the pilot will feel the pain too; when the pilot cries, the robot will shed tears too. Comparing with Cronenberg, this is an extremely non-scientific and unrealistic concept of a machine, but I guess that this approach to the robot as a human extension actually allowed the viewers to relate to Mazinger or Grendizer and helped making them so popular worldwide. And even if I said that this is a “non-scientific” vision, if we look at contemporary cybernetics, the scientists and engineers of today are putting all their efforts not in potentiating the robots’ functions or powers, but in making them more human, either in their movements, reasoning and facial expression. Old Sci-Fi books and movies used to depict the future society as one where the human beings, acquainted to interact with machines, lose all their feelings and become just as dry and cold as real machines; but if we look at today’s reality and at the direction that cybernetic studies are taking, I guess that a human-like robot as Mazinger or Grendizer has all the chances to become a reality in our future.

Westerners were fascinated by both Japanese culture and Egyptian culture because they were the oldest civilizations of the world. How do you interpret the reverse influence of Manga and Anime on the western world?

It is a very peculiar feeling. I mean, nobody, really nobody of us would have ever thought that Japanese comics and animation would have reached one day to foreign audiences. I didn’t even know that my animation characters were broadcast in Europe and Asia, and I learnt about the Middle East just last year! When we created our characters – and by “we” I mean myself and all my fellow comic artists – we conceived them only for the domestic market. Lately, as the Japanese market shrinks because of the very low birth rate, many authors have started creating stories meaning to have an International appeal, because they need revenues from foreign markets to recover their investments; but it is funny how many of these stories fail to succeed abroad, while stories like “Mazinger” or “Grendizer”, which have been created only and exclusively for Japanese audiences, are eventually so successful with foreign readers and viewers!

I think that I must be very proud of their success, because I remember when twenty years ago a French director told me that, before seeing “Grendizer”, he thought of Japanese people only as “Economic Animals”, harsh, un-hearted and inscrutable samurais whose only interest was to make money and invade the world with their technology products: only through “Grendizer” he could eventually discover that Japanese share the same feelings of love, friendship and brotherhood of any other human being. So, I believe animation has helped the world to discover the real soul of Japanese people and their culture, more than anything else. For the same reason, I am looking forward to an original Arab entertainment industry to develop and extend its reach internationally, because I believe it will eventually help in tearing down all the walls and the barriers created by centuries of misunderstanding or biased reports by Western media have diffused about the Arab culture.

In Shin-Mazinger, you have chosen to retell the story of Koji and Mazinger in a more adult and darker approach (noting the colors and design of characters) not to mention some graphic violence too. By doing this, would you like to address a more mature public with Shin-Mazinger.

Mazinger was born as a comic book, but when it was decided to transpose it to animation, the production studio lamented that they needed to rewrite some characters and change the original design of Mazinger because, for the technology of the early Seventies, it was too complicated. So, the original Mazinger series was very enjoyable, but it ended being fairly different from what I had conceived. This new series is much more similar to my comic book, but you are perfectly right to say that it has a darker touch. This depends much more on a choice by the animation director than on my personal decision, but I liked his idea and his skills, so I gave him total freedom to develop these settings at his own will. Also, this new animation was broadcast in Japan after midnight, so it is targeted to the adults who saw the original “Mazinger” when they were kids and not to today’s kids. For today’s kids, I guess I should plan a totally different story.

If a Mazinger or a Grendizer live action film would be made in the future. Would you like to produce through your company Dynamic Animation it or you would like to sell its rights to American companies like Transformers? Would you prefer Japanese or Western actors to perform the main roles?

I receive many offers even from major movie studios to transfer “Mazinger” or “Grendizer” to the big screen for live action movies. Until today I refused most of them because they would limit very much my control of the story, and also because I didn’t think that computer graphic has evolved enough to depict my characters well enough; but today I believe we can definitely make a convincing “Mazinger” or “Grendizer” movie by mixing live action and CG. The problem is that such a project would be so expensive that it would be impossible to produce it in Japan; also, since a child I was used to love Western movies, and the design of my characters have been affected by the look of Western actors and actresses, so I guess I would prefer a Western or mixed staff to a totally Japanese one. Anyway, the real problem is the budget. If any Middle East fan of “Mazinger” or “Grendizer” has the will and the means to invest in such a project, please contact me (laugh).

Finally, I would like to know about your roundup thoughts about this Arab voyage, especially in Egypt. What have you imagined and what have you discovered with Egyptian young students of Animation?

It’s been a trip of discovery. Images of the Middle East we get on Western or Japanese media are totally different from the reality I had a chance to see during this visit. People of the Middle East are incredibly warm, welcoming, and I have been overwhelmed by their love for “Grendizer” and “Mazinger”. Also, I had a chance to visit four totally different countries, Jordan, Kuwait, Egypt and Dubai, just to find that you cannot speak of an Arab world as something indistinct, but there are many different societies that compose such world. Media depicts the Arab world with the images of the streets of Gaza, or of the 911 attacks, and I think this is a very reductive, biased and, consequently, abusive way to convey the real spirit of the Arab culture to the world. As I said, I am looking forward to a genuine Arab entertainment industry to spread to the world in order to help other cultures tear down the walls of misunderstanding. From this point of view, I can’t wait for seeing the works of Egyptian young animators and other valuable young artists of the Middle East. They carry on their back the burden of thousands of years of history and of one of the most fascinating cultures in the world, and it’s only up to them to define how to deliver it to the people of the whole planet; but I had a chance to appreciate their skills and I know that they can do it!